by Dr. Joanna Sliwa, Claims Conference Historian

Accusations

An epidemic swept through continental Europe in the 14th century. About 25 million people, or one third of the European population, died from the bubonic plague, also called the Black Death. It was caused by a deadly bacteria brought from battlefields and spread through the movement of people across geographic borders. In a situation without knowledge about what was happening and why it was occurring, Christians hurled accusations against Jews. Those people searched for religious answers to explain the devastating reality unfolding before them. Although Jews, too, were dying in great numbers, Christians positioned Jews as culprits for poisoning wells and alleged that Jews knowingly and purposefully created an epidemic. This was an outrageous accusation that had real and tragic consequences. Local rulers expelled Jews from towns and villages. Jews fell victim to massacres in areas in today’s France, Spain, and Germany.

Literature

One the most acclaimed and studied pieces of literature also contains antisemitic tropes. William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice was published at the end of the 16th century. The main character, Shylock, is portrayed as a moneylender, an occupation traditionally held by Jews in the Middle Ages and the early modern period. His greed, Shakespeare shows, leads to Shylock’s demise. The Christian who borrowed money from Shylock manages to outwit “the Jew.” And the Jewish man is faced with a choice to redeem himself: lose his assets or convert to Christianity. Depicted as a materialist above all, he chooses conversion.

This story may be read as a larger commentary on the society of that time, on the role of Jews in it, and on Jewish-Christian relations. However, the story of Shylock was used and abused over the ages to send a message to various audiences. It has inspired illustrations, such as the one pictured here, and plays. Nazi sympathizers in the 1930s staged performances based on Shakespeare’s play to impress upon the German people the stereotypes of Jews as harmful to the society and to the Nazi imagined racial community. The example of The Merchant of Venice shows us that classic literature is not immune to antisemitism. When read without a critical lens, it could strengthen and promote harmful ideas about Jews as a group. This example also shows us the power of the written word to shape attitudes and thinking about minority groups.

Chants

Emancipation for Jews, meaning Jews’ efforts to obtain rights equal to those of non-Jews, was undertaken in German lands in the 19th century. However, this occurred not without opposition from many non-Jews. In 1819, Jews endured a series of riots. “Hep! Hep!” served as the rallying call to attacks on Jews. These two words were enough to spark violence against Jews whom some non-Jews perceived as wielders of power and financial exploiters.

Europeans in the 19th century were experiencing a range of difficulties, with famine and wars leading to fear, deaths, and the need to find a culprit for the injustices. Jews emerged as targets throughout German lands. This unrest among the population prompted the local rulers to temporarily disengage from granting Jews rights. Jews in German lands persevered. Yet, the riots impeded Jews’ efforts to obtain equal standing with other residents of their homeland.

As the “Hep! Hep!” riots show, words carry meaning. This seemingly innocent phrase could have derived from the Crusaders’ proclamation: “Jerusalem is lost.” Another story ties the phrase to the word “Hebrews.” Yet a different explanation traces the rallying call to the exhortation of sheep herders. Despite the unclear origin, “Hep! Hep!” became a recognized chant across German lands to incite aggression against Jews.

Exclusionary Statements

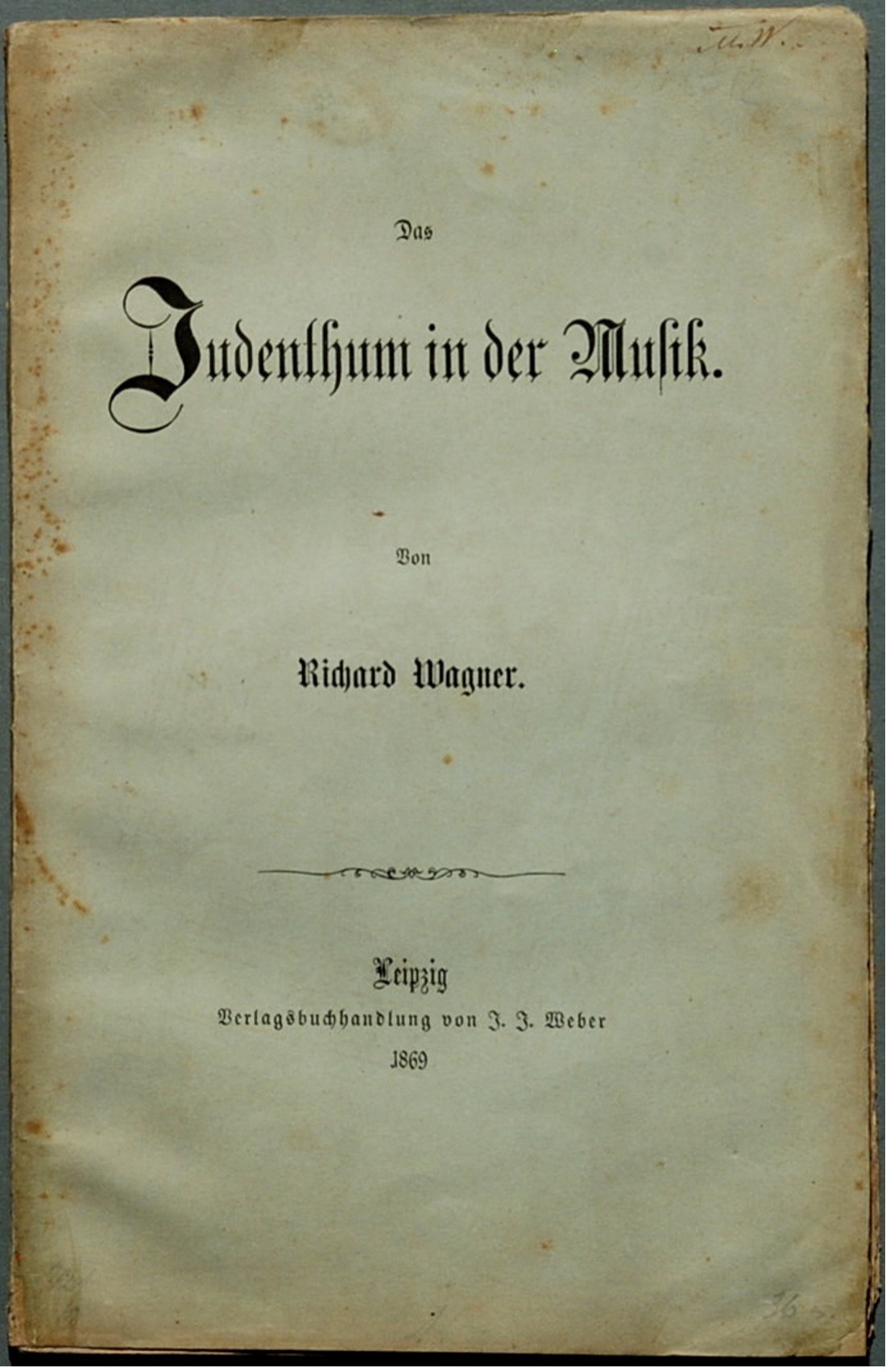

In 1850, the acclaimed German composer Richard Wagner penned the essay, “Jewry in Music.” In it he depicted Jews as an alien and inferior element in the society. He argued that Jews, posing as assimilationists, infiltrated Europe. Wagner pointed to the decay of art resulting from the power that he believed Jews wielded. Wagner’s statements aimed to exclude Jews from the realm of art and the larger German community. For Wagner, language symbolized the soul of the nation. He proclaimed that Jews lacked an inner metaphysical understanding of the German language, and thus could not fathom the Volksgeist, the spirit of the nation.

Wagner’s exclusionary statements in “Jewry in Music” positioned Jews as deceptive outsiders and created an “us versus them” narrative, in which the German people were superior. Music, according to Wagner, served as an area that showed the supposed inferiority of Jews. His solution called for a German emancipation from anything connected to Jewishness. That, based on Wagner’s antisemitic thinking, meant for the German people to show passion, shed their efforts to mimic Jews, and give up their infatuation with material things.

While centered on art and perceived Jewish influence, Wagner’s statement also reflected a concern about the German lands. Wagner embraced the idea that once the enemy, meaning the features that he considered Jewish and that crept into German community, were eradicated, then Germany would be restored (Germany was created as a country only in 1871). Wagner’s exclusionary ideas appealed to many in a society going through great changes and faced with many unknowns.

Fabricated Stories

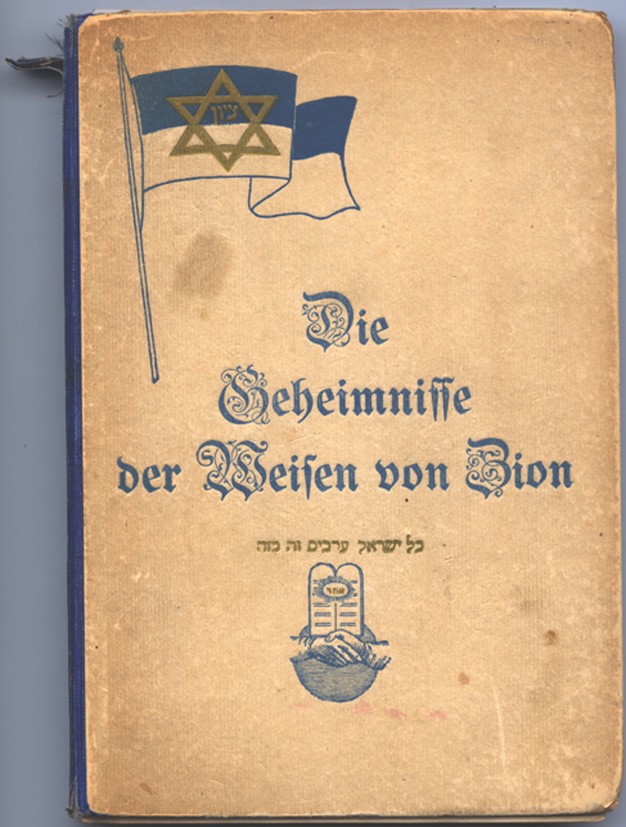

In 1903, a Russian newspaper published a series titled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The 24 chapters aimed to sow distrust of and hatred toward Jews. These were supposedly minutes of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders at the First Zionist Congress in 1897. This completely fabricated story drew from fears, prejudices, and lies. The text introduced a conspiracy theory to show the alleged sinister plans of Jews to take over the world. By 1907, the text reached countries outside Russia. Among the publishers of this blasphemous text was Henry Ford in the United States. In 1920, Ford published the book, The International Jew. He curried favor for it with top Nazi adherents in Germany, including Adolf Hitler and the Nazi propaganda expert, Joseph Goebbels.

By 1921, British journalists had proof-checked the text and exposed it as a hoax. And yet, The Protocols remained the most enduring slanderous, virulently antisemitic text. They inspired Hitler’s ideas about how the world functioned and about the danger that, to him and in his worldview, the Jews posed. The Nazis continued to peddle the mythical character of a world Jewish cabal that conspired to dominate the world. To the Nazis, this image of the Jews explained the need to eradicate Jews as a people from society.

The power, pervasiveness, and persistence of the myth perpetuated in The Protocols has been one of the most dangerous in modern history and has incited violence, pogroms, and antisemitism across the world.

Blood Libel

Throughout Europe, many rulers, and the populations they governed, saw Jews collectively as a threat. In the Russian Empire, the hatred of Jews merged anti-Judaism with antisemitism. On Easter Sunday in April 1903, non-Jews staged a pogrom, an organized assault, against Jews in the city of Kishinev (today: Chisinau, Moldova). It started with a blood libel, an accusation that Jews kidnapped Christian children to kill them and use their blood in matzah, the unleavened bread that observant Jews are religiously commanded to eat during the holiday of Passover. Christian rioters killed about 50 Jews, wounded hundreds of Jews, and vandalized many Jewish homes and businesses. Jews were not protected by the authorities. They were seen as a foreign element, as an enemy that conspired against non-Jews. Often, the Church fanned the flames of the damaging and deadly myth. Its leaders did not publicly oppose the blood libel and some churches displayed images showing alleged Jewish religious practices, thus legitimizing them.

The myth that Jews killed Christians and then used their blood in ritual practices was not new. The earliest case of the blood libel in Europe occurred in 1144 in Norwich, England. Since then, such accusations against Jews proliferated across Europe. But they also expanded to the Arab world. Blood libels were usually, but not always, tied to Easter time, implying that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus. Therefore, the charge of the blood libel strengthened the dangerous lie that Jews were Christ killers. The blood libel and the ensuing pogrom in Kishinev was a transformational event in 20th century Jewish history. Its aftermath prompted the revered Jewish poet Hayim Nachman Bialik to chronicle the destruction of Kishinev Jews. The massacre that unfolded on two April days in 1903 sent shockwaves across Jewish communities worldwide.

Although a hoax, as Judaism forbids the consumption of blood, the legend lived on. The Nazis exploited the fraudulent accusation against Jews by inserting it in propaganda. The front-page article of the most popular issue of the viciously antisemitic paper, Der Stürmer, of May 1939, depicted an imaginary ritual that utilized the blood of Christian children. Images and texts such as this one solidified bias toward Jews and affected the treatment of Jews.

Front page of the most popular issue ever of the Nazi publication, Der Stürmer, with a reprint of a medieval depiction of a purported ritual murder committed by Jews. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Virginius Dabney

Words and Ideas Lead to Action

Derogatory terms referring to Jews exist in various languages. Historically, they have emerged for political, religious, cultural, economic, ideological, and social reasons. They were used in everyday life by ordinary people, by rulers and thinkers, politicians, and by religious leaders. What the disparaging terms had in common were the efforts to denigrate Jews on both individual and collective levels. The goal was to present Jews as outsiders. Often, the aim was to legitimize assaults against Jews.

People have created terms deriving from the word “Jew” and marked them with negative connotations. This has served to diminish Jews as a people and present them not as individuals but as a mass. Then too, it fomented imagination about the supposed negative influence of Jews on a society. Another reason had to do with efforts to ridicule Jews, and thus elevate oneself and one’s ethnic, religious, national, or social group. Terms that derived from words referring to Jews were imbued with additional, hidden meaning. In this way, pejorative terms about Jews have continually amplified antisemitism.

Pejorative words were hissed at Jews by their non-Jewish neighbors and peers. Verbal attacks often led to physical violence.

Before the Holocaust, Henry Rosen lived in Czortków, Poland (today: Chortkiv, Ukraine). Many years after the war, he recalled in an oral history,

“I was seven years old and in first grade, when a Gentile boy was throwing stones at us and they were singing ‘Żydzi zabili Chrystusa,’ ‘the Jews killed Jesus.’ This was full of hatred. They took it from the Church and from the parents that we are bad people and that we killed Jesus. They didn’t know that Jesus was a Jew.”

Henry Rosen, USC Shoah Foundation, interview 35502, recorded on November 10, 1997, segments 8-9.

Boycotts

To retaliate against what the Nazis perceived as bad press promoted by Jews outside Germany, the Nazi regime responded with boycotts of Jewish-owned businesses. To the Nazis, Jews were a race and, as such, German Jews were responsible for the behavior of Jews elsewhere in the world. This belief also conflated Jews with an international, cosmopolitan entity that was supposedly threatening Germany and the German people.

On April 1, 1933, members of the Nazi Storm Troopers stood in front of Jewish-owned stores and businesses throughout Germany, blocking entry of non-Jews. Members of this paramilitary group painted the Star of David, and other antisemitic imagery, on windows and doors of Jewish establishments, marking the “prohibited” places for non-Jewish Germans. The Storm Troopers held signs urging, even ordering, the passersby not to buy from Jews. In this way, Jews were visibly othered.

This economic boycott was not successful in economic sense, but it sent a message. To the German Jews, this boycott meant that they were now outside the protection of the law. Many ordinary Germans, on the other hand, felt uncomfortable with the street violence against their Jewish neighbors. The Nazi regime pondered how to both guarantee public order and fuel antisemitism. The short-term failure of the Nazi measure was that ordinary Germans supported the boycott less enthusiastically than the Nazis had anticipated. The long-term success of the action was that the boycott prepared the German people for state-sponsored antisemitism and violence and made the Nazi government realize the need for a more methodical approach.