by Dr. Joanna Sliwa, Claims Conference Historian

Words of Rejection

“I will never forget this. One of my non-Jewish friends, that I used to go to school with and play with – and she was also a neighbor from the next building – when I approached her, she said ‘I cannot play with you anymore because you are Jewish.’ I came home crying. I wanted to play with her, and I couldn’t.”

Frances Gelbart, Interview 12003, Shoah Foundation, 1996, segment 13.

That is how Frances Gelbart recalled a major change in her life as a young girl. Frances was ten years old when the German army entered her hometown of Kraków, Poland, on September 6, 1939. The words that her friend, a non-Jewish Polish girl, said marked Frances as different, as an enemy even. What did Frances do to deserve this? Why was she suddenly targeted as the “other”? Frances and her friend, who until then had spent time together simply as Krakovian girls, now were divided based on religious affiliation and the racist laws that the German occupiers established. The rejection that Frances experienced, and the demarcation imposed by the authorities and the Polish neighbors, defined the lives of Frances and all the Jews of Kraków.

View the timeline of Antisemitism in Europe leading up to the Holocaust

The curt words from a supposed friend left Frances flummoxed. It was the first time Frances was directly confronted with antisemitism. Frances later understood that it was not her friend who created the separation between them. Her Polish friend was not the one whose prejudice motivated her to cut ties with her Jewish peer. Rather, it were the adults, the parents of her friend who imparted anti-Jewish bias in their daughter and instructed her to cease her friendship with Frances simply because Frances was Jewish. This lack of solidarity with Jews, especially in times of crisis, was not the outcome of the German occupation of Poland. Years of enmity against Jews that many Polish people harbored, and regarding Jews as the quintessential “other” created rifts during the Holocaust that had an immediate effect on the way Jews were persecuted and how their neighbors reacted to the Jews’ plight. The words that Frances heard from her friend underscored a real sense of betrayal and confirmed Frances of her status as an outcast in her own city and country, and among people she thought she belonged to.

Bullying

In the first days and months of the German occupation of Kraków, Poland (which occurred on September 6, 1939), German soldiers harassed those most visibly Jewish to them – pious Jewish men. For example, they cut the religious men’s beards on the street. They forced the men to march or run through the streets with their arms raised. Humiliating Jews was done in broad daylight.

Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Instytut Pamieci Narodowej

“The Poles used to stand on the sides, applaud, and laugh.”

Frances Gelbart, Interview 12003, Shoah Foundation, 1996, segment 32.

That is how Frances Gelbart, who was ten years old when World War II broke out, recalled how non-Jewish Poles mocked the Jews in public. Those were key moments. To the German authorities, these situations sent a message how the local non-Jews would react to the gradual, yet swift, persecution of Jews. To the Jewish Krakovians, such as Frances, witnessing such scenes instilled shock, terror, and a sense of betrayal. That is not how Frances expected her neighbors to respond to the public abuse of the city’s Jewish residents.

The exclusion that Jewish Krakovians felt and experienced from their non-Jewish neighbors was magnified when the German authorities gave Jews only seventeen days to move into the ghetto. Jews endured great hardships. They were forced to leave their homes and most of their belongings, or sell other items to the non-Jewish Poles, often for prices below value. Jewish children had to part with their toys and other cherished things. Families were separated, as not all Jews from Kraków were allowed to enter the ghetto; the German authorities expelled thousands of Kraków Jews to limit the presence of Jews in the capital of the General Government (German-occupied Poland). Photographs of the expulsion of Jews to the district of Podgórze where the ghetto was located show Jews carrying items and hauling carts with furniture and other items that they were permitted to take.

The forced relocation of Jews took place in full view, during the day. Rena Finder, who was twelve years old in March 1941, recalled,

“We just walked, and the Polish people stood on the sidewalk and they were yelling ‘Good riddance!’ ‘Go! Don’t come back! Such hate. It was such hate. Such unbelievable hate. You walked and you wondered: what did you do? You never did anything to those people. And they hated you.”[3]

Rena Finder, Interview 21482, Shoah Foundation, 1996, segment 10.

The words that Rena and other Jews like her heard coming from their non-Jewish neighbors further confirmed them of their exclusion from the broader Polish society.

The Antisemitic Mantra

“The Jews are Our Misfortune!” This slogan, printed on each issue of the virulently antisemitic Nazi tabloid, Der Stürmer (The Attacker), screamed at passersby and customers of press stands in Germany. The tagline of the newspaper was supposed to solidify the imagery of Jews as the enemy of the “Aryan” people, the cause of all ills in the Germany society. However, these words were not invented in 1923, when the paper was first published by Julius Streicher. Rather, the phrase was borrowed from Heinrich von Treitschke, a German historian and nationalist politician, who coined it 1879.

Der Stürmer strove to channel Nazi propaganda to the masses. The mantra blaming Jews for every supposed tribulation afflicting the German society (and the world) was usually accompanied with a virulently hateful and graphic cartoon. It presented Jews as predators, exploiters, and destroyers. The caricatures portrayed Jews with pronounced physical features and contained symbols that cast the Jews as communists, capitalists, and cosmopolitans, but also dangerous and inhumane figures. The paper included articles deriding Jew, that, together with the portrayals of Jews, image captions, and the front-page slogan, were supposed to convey simple and direct messages to the German public. By 1938, year of the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht), the paper not only spewed hatred, but also turned to incite the German people to the physical attacks against Jews. The circulation of the paper reached its peak that year, with nearly half a million copies published.

The paper and its antisemitic mantra continued into 1945 when all but a few Jews remained in hiding, living under a false identity, or in concentration camps. Streicher, the creator and publisher of Der Stürmer was hanged in 1946 after he was found guilty by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany, for his role in inciting to genocide.

Slogans and Banners

“Day Without Jews. We Demand an Official Ghetto” read the banner of Polish students hoisted at the Lwów Polytechnic in Poland in the 1930s. This public display of exclusion of Jews in interwar Poland was connected to several factors, all underscored by deep divisions and anti-Jewish prejudice. Segments of the Polish population wanted to ensure positions in the professions specifically for non-Jewish Poles, especially considering the economic crisis that loomed over Poland. Then too, non-Jews often did not see Jewish Poles as belonging to the same nation – to them, Jews were the quintessential “other.” The anti-Jewish legislation in Nazi Germany that increasingly excluded Jews from all areas of German public life, emboldened Polish nationalists both to promote their exclusionary slogans and to take action against Jews.

Members of Polish extreme nationalist groups, such as the National Radical Camp (which continues its activity in today’s Poland), demanded not only restricting the numbers of Jewish students admitted to Polish universities (numerus clausus), but also instituting segregation in lecture halls (ghetto benches for Jews). The Lwów Polytechnic introduced a separate area for Jewish students to sit in 1935. A year later, following much violence against Jews and protests from Jewish students and leaders, the administrators of the school retreated from the policy in 1936. However, efforts to institutionalize ghetto benches, agitations against Jewish students, blocking them from entering university premises, and physical attacks against Jewish students and professors continued throughout Poland in the 1930s.

The banners with hateful messages and the slogans screamed by non-Jewish Polish students and members of Polish nationalist groups positioned Jews as belonging outside the Polish national community. This treatment started with words and progressed into actions that harmed Jews’ sense of security in their own country and endangered their physical wellbeing. These notions about Jews as being different and not really part of the Polish people affected the responses of ordinary Poles to Jews’ situation in interwar Poland and to the Jews’ plight during World War II.

Messages of Division

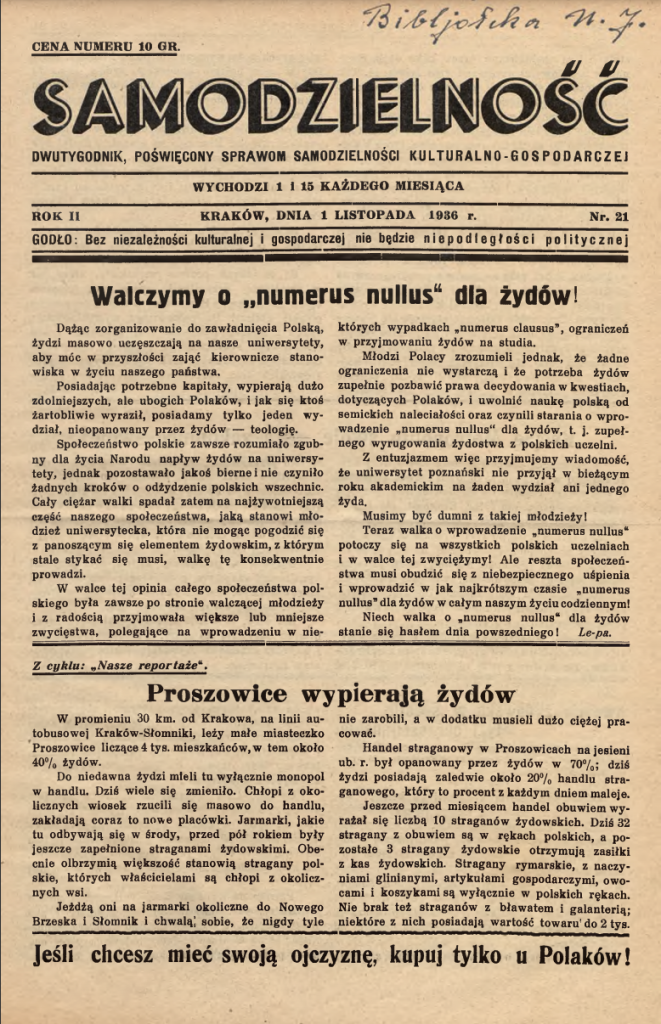

The Polish press channeled calls for the economic exclusion of Jews in interwar Poland. “Proszowice are ousting Jews,” an extremist Polish biweekly newsletter Samodzielność (Autonomy) reported in fall 1936. The town of Proszowice, near Kraków, prided itself, the author claimed, on pushing Jews out of the market sphere and replacing Jewish-owned stores and stalls and other businesses with those owned by non-Jewish Poles. Polish nationalists, and segments of the non-Jewish Polish population, saw Jews as exploiters of Poland and of non-Jewish Poles, and as competitors to eliminate. In fact, all texts in this issue of the newsletter dealt with instilling messages of division between Jews and non-Jews and condoning the efforts to segregate Jews in public life.

The caption at the bottom of the front page reminded its readers: “If you want to have your own homeland, buy only from the Poles!”